The DSM-5-Text Revision is upon us. The DSM, long regarded as the bible of the mental health field, has a long and controversial history. Every mental health professional you meet is bound to have many criticisms of the manual that provides us with the penultimate list of mental health diagnoses with the criteria needed to meet the “threshold” for diagnosis—and I am certainly one of them.

My criticisms aside—it is important for us to understand that the DSM is created by mental health professionals, and it attempts to be reflective of our current culture and social landscape. I picture these decisions being made in a stuffy board room by a bunch of old dudes who look like Freud (this is may or may not be accurate).

The problem lies in the fact that the DSM is consistently “a day late and a dollar short”. The text revisions and new editions always lag far behind clinical and social acceptability. An example of this? This text revision is the first one to use the phrase “gender-affirming medical procedure” rather than “cross-sex medical procedure”. See what I mean? The socially acceptable and trauma-informed terms that become the standard for us often take years, or even decades, to make it into the DSM.

So What About Grief?

This is the first edition to include the diagnosis “Prolonged Grief Disorder”. The criteria include “a persistent grief response for a duration longer than 12 months (6 months for a child)” and “symptoms that significantly interrupt a person’s day-to-day functioning”. My first reaction reading the new criteria was, “has no one in that room ever experienced grief before?” And my second reaction? I was pissed.

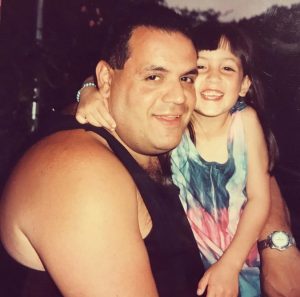

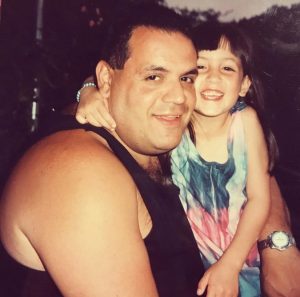

On March 21, 2015, my dad died at 54 from renal cancer. I was 21 when he was diagnosed, just 2 months after my college graduation. He passed when I was 26. The formative years of my 20s were spent learning things that a 20-something year old girl really shouldn’t have to know—what is a PET scan? There are types of chemo that don’t make you lose your hair? How does cancer travel from a kidney to a lung? You get tattooed for radiation? It’s possible for a treatment to start working and then stop working?

My dad had a “good” 5 years. He was able to work much of that time, he didn’t spend long periods of times hospitalized, didn’t lose his hair (always a point of pride for him) and we were able to go on a handful of family vacations. But living with stage 4 cancer is like living in the shadow of a volcano—never knowing when everything would explode and the landscape would change forever. And today marks 7 years since that volcano erupted.

Grief is an inevitable part of life. It is as much an emotional experience as it is a biological one. Elephants, gorillas, dolphins, dogs, whales, and giraffes are only a few of the species that have been observed to grieve the loss of loved ones. Some animals grieve until the body of their companion starts to decompose. But others—elephants particularly— continue to honor the bones of their lost companion long after the rest of their body is gone.

Much like in the animal kingdom, the way we grieve is impacted by our biology, our attachments, our culture, and how much grief we’ve experienced throughout our life. As we find ourselves on the heels of a pandemic, we know that Americans have experienced a tremendous amount of loss. These losses are complicated by many other factors: shocking losses, not being able to say goodbye to loved ones who died in isolation, not experiencing the “rituals” of death that we find comfort in (ie: holding wakes, funerals, sitting shivah, etc.) The Prolonged Grief Disorder diagnosis does nothing to recognize these complications, nor does it provide the important nuances and contexts that we need in order to understand these complexities.

How productive would it be for me to diagnose Prolonged Grief in a someone who lost a sibling to COVID and didn’t get to hold their hand or tell them they loved them before they died? Or how about a woman who tragically lost both parents in her teen years? Or the couple struggling through multiple miscarriages, desperately trying to achieve their dream of having a family? What will this do for us? At best, it will state the blatantly obvious. At worst, it could stigmatize and create a sense of shame for the griever. “Why am I stuck in ‘prolonged grief’? Why does my therapist think I should be over this? What is wrong with me? Why can’t I just get over it?” This diagnosis has a potential to do harm, and that is where every clinician needs to proceed with absolute caution.

Why Pathologize Something That Is A Natural Part of Life?

One answer to this comes down to the bureaucracy of mental health treatment. Call me cynical, but it’s impossible to have a conversation about the DSM without considering that insurance companies and third-party payer organizations have a MASSIVE influence on the way treatment is shaped in this country. While having a diagnosis for something as natural as grief feels (and is) ridiculous—it means providers can classify someone’s need for care as “clinically significant”. This can be used to bill insurance companies and “justify” various levels of care for people who are experiencing symptoms.

The issue is going to come down to whether insurance companies and their “doctors” (I use quotations because a “doctor” who never lays eyes on someone being the deciding factor on whether something is covered makes me want to barf) will determine if this diagnosis is “serious” enough to be covered. Insurance companies will ask for documentation of symptoms. Inevitably, they will ask “why isn’t this person getting better if they’ve been in therapy for 6 months?”, and they will quantify how many sessions they think are “enough” before cutting coverage. To be clear, this is not a new issue—it is already the standard practice of insurance companies.

There is a Bright (Or Less Dark) Side

My other answer is less cynical (I promise lol). The DSM has always provided a framework for diagnoses, especially for new clinicians. I remember pouring over the DSM-4 in my early days of internship, looking carefully at the criteria to decide whether someone met criteria for Major Depression, or teasing out the difference between Bipolar I and Bipolar II.

By having this diagnosis, we are able to understand and validate just how serious grief can be. Clients who otherwise would be thrown into Adjustment Disorder, Major Depression or Posttraumatic Stress now have a diagnosis that fits a little better. New clinicians or clinicians who are not familiar with grief work will be able to recognize the impact that grief has in our lives as grievers. We can now help people receive FMLA with a diagnosis that is more accurate. And we can tailor more trainings and supervision opportunities with this diagnosis in mind.

Context is Key

It is crucial to remember that the DSM is supposed to *guide* clinicians. There are many people walking around with symptoms that fit a diagnostic criteria, but that does not necessarily mean a diagnosis is appropriate. Good clinical judgment has always been an absolute requirement to be a good therapist. We are trained to understand the context in which people exist—would my ancient off-the-boat Italian aunts who dressed head to toe in black for the rest of their lives after their husbands died benefit from a Prolonged Grief diagnosis? Nope.

We also have to remember that grief changes over time—but that doesn’t mean that it always gets better. The first year that my husband and I bought our house was the hardest year I had since my Dad died. Every faucet that needed fixing and every hole that needed patching would leave me in tears, or angry and cursing him in my head for not being here to help us with all the things that I knew he was supposed to be here for. I could picture him vividly in my head trying to give us directions while we figured something out, drawing on the years that my brothers and I would have the dreaded job of holding the flashlight for him (if you know, you know) while he would talk (and yell and curse) us though what he was doing.

Grief is not Shameful

Grievers will know what I mean when I say that grief makes us feel like we have lived two lives. Our life before the loss where, we felt safer and more naïve to the suffering of life; and life after the loss—where we carry the weight of grief, when it makes us grow up faster and become a bit more jaded.

When I work with grieving clients, I draw on my own experience to help guide their grief journey. We treat grief like a roommate that we are reluctant to allow into our house—we make space for it, but it’s taste in décor is awful and we wish they would move out. However, we cannot deny grief because it is there whether we like it or not.

Experiencing loss changes us in our core. There is no timeline for grief, and there is no way to predict how we will feel. There are times when everything is going great, only to have a song, or a smell, or a memory pop into our heads, and then suddenly it feels like the ground cracks open and swallows us into the pit of despair. But we can roll with grief. Because the depth of our grief is a reflection of the depth of our love.